Belting Won't Wreck You

Belting is a highly pressurized way of singing. Renown voice scientist, Ingo Titze, describes it like this:

In school, students are exposed to classical solo singing and choral singing vocal techniques. Thus, their "homebase" for singing includes: a lifted soft palate, a long vocal tract, neutral larynx, stable jaw (not overly lowered). This approach to singing will unfortunately become a hindrance in musical theater since the aesthetic goals of the genre are different than that of classical singing... but classical singing will likely "feel" more comfortable and instinctive *if* a student has only been exposed to that type of singing.

Concession: belting is inherently more dangerous than classical singing. Why? Because, as mentioned before, it is a highly pressurized way of singing. BUT that doesn't mean that belting will automatically obliterate one's cords like Crossfit or extreme sports won't automatically wreck your body. You just have to understand your body's mechanics and limitations in order to produce the sound efficiently.

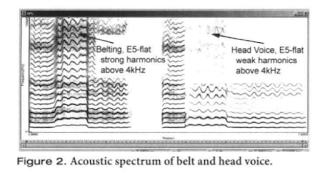

Scientifically speaking, belting contains a less clear/more dense harmonic spectrum which you can see in Scott McCoy's Figure 2 below. The spectral analysis of belting is far darker than that of head voice which means that the formants (or higher pitches perceived above) are less clear than that of a classical head voice. McCoy mentions in his initial article that belting contains more "acoustic energy (defined as the disturbance of energy which passes through matter in the form of a wave) than that of head voice which means, we the listeners, perceive a brightness in the singer's quality when they're belting, as opposed to a roundness in classical singing.

Pedagogues go back and forth about the height of the larynx in belting and what's healthy and what's not. Inevitably, as you get higher in your belt, the larynx will raise a fraction of an amount. This is okay. You will not die. You will not wreck your voice. Belting is not the enemy. Let's stop demonizing it.... especially when your choir kids are learning how to do it healthfully with their private teachers.

***Charts are by Scott McCoy.

Belting is a sound that is characterised by a shortening of the vocal tract at the higher pitches. The shortening creates differences in the sound wave reflections that strengthen a particular rich colour in the tone (for you voice nerds out there, this tone is found through the strengthening of the 2nd harmonic). In order to get this shortening of the tract, a singer must raise their larynx, widen their lips and lower their jaw. This all helps to shorten the tract, tuning in to the belted sound.

In school, students are exposed to classical solo singing and choral singing vocal techniques. Thus, their "homebase" for singing includes: a lifted soft palate, a long vocal tract, neutral larynx, stable jaw (not overly lowered). This approach to singing will unfortunately become a hindrance in musical theater since the aesthetic goals of the genre are different than that of classical singing... but classical singing will likely "feel" more comfortable and instinctive *if* a student has only been exposed to that type of singing.

Concession: belting is inherently more dangerous than classical singing. Why? Because, as mentioned before, it is a highly pressurized way of singing. BUT that doesn't mean that belting will automatically obliterate one's cords like Crossfit or extreme sports won't automatically wreck your body. You just have to understand your body's mechanics and limitations in order to produce the sound efficiently.

Scientifically speaking, belting contains a less clear/more dense harmonic spectrum which you can see in Scott McCoy's Figure 2 below. The spectral analysis of belting is far darker than that of head voice which means that the formants (or higher pitches perceived above) are less clear than that of a classical head voice. McCoy mentions in his initial article that belting contains more "acoustic energy (defined as the disturbance of energy which passes through matter in the form of a wave) than that of head voice which means, we the listeners, perceive a brightness in the singer's quality when they're belting, as opposed to a roundness in classical singing.

Another interesting fact is that in belting, the "closed quotient (CQ)" is higher than that of head voice. You can observe this in Scott McCoy's Chart below. We can see that the belting charts waves are longer horizontally, meaning that the vocal folds stay closed longer during belting than they do in classical singing. What the heck does this mean? It means that there is a build up of pressure below the vocal folds. So, as you can imagine, belting is going to be more fatiguing than head voice. Thus, belting a phrase over and over again is not the greatest idea.

Pedagogues go back and forth about the height of the larynx in belting and what's healthy and what's not. Inevitably, as you get higher in your belt, the larynx will raise a fraction of an amount. This is okay. You will not die. You will not wreck your voice. Belting is not the enemy. Let's stop demonizing it.... especially when your choir kids are learning how to do it healthfully with their private teachers.

***Charts are by Scott McCoy.

Comments

Post a Comment